Click here to watch this video on our YouTube channel. (Live stream will begin at 10am on Wednesday, May 6th, 2020).

People’s book for the Divine Liturgy

Divine Liturgy Propers for Mid-Pentecost Wednesday

Click here to watch this video on our YouTube channel. (Live stream will begin at 10am on Wednesday, May 6th, 2020).

People’s book for the Divine Liturgy

Divine Liturgy Propers for Mid-Pentecost Wednesday

Click here to watch a video of this service on our YouTube channel. (Live stream will be a 7pm on May 5th, 2020)

Vespers Propers for Mid-Pentecost Wednesday

Click here to watch a video of this service on YouTube (live stream begins at 9am, Tuesday, May 5th, 2020)

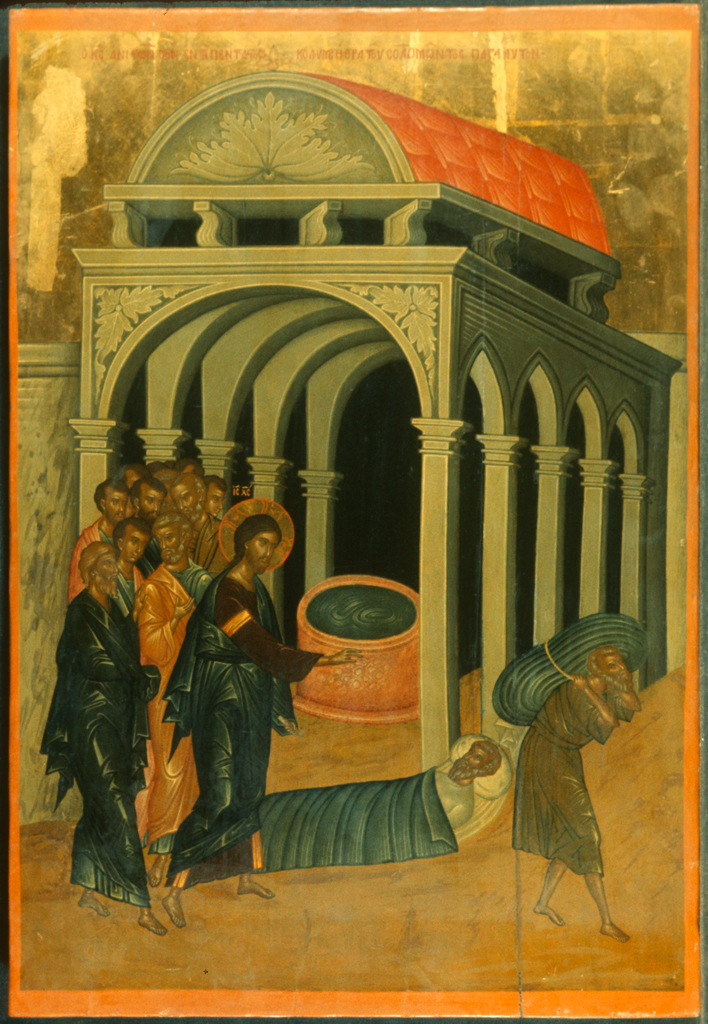

The sheep pool by which Jesus heals the paralytic man (John 5:1-15) is an image of baptism. This connection is made at Matins for the Sunday of the Paralytic during the first ode of the Canon. The reader chants, “Once in the pool at the Sheepgate, an angel descended from time to time, healing one person at a time; but Christ now purifies an innumerable multitude by divine baptism.”

We’ve been talking a lot about baptism, lately. Perhaps you’ve noticed. Many of the readings and hymns these days focus on baptism. And this makes sense. We are in the midst of Pascha, which is the greatest baptismal feast.

It would help us to remember our baptism every day. Baptism makes us who we are in Christ. I’m not exaggerating. We are baptized into Christ. We become – by baptism – members of his body, which is the Church. We remain the Church, and members of his body, even when we cannot assemble in these days, by virtue of baptism. It’s easy to forget that we are a baptismal people if we do not often think about baptism. Baptism is our primary business. It’s what we’re all about.

And so, throughout Pascha, the liturgies and readings turn our minds again and again to baptism. Let us meditate throughout this time on what baptism means for us, where it comes from, and how it shapes our lives.

Today’s gospel offers us another chance to do this. But it’s not readily apparent, at least not to me. When I read this passage, my thoughts do not go first to baptism – but rather to the miraculous healing the Lord works – or perhaps to the man’s thirty-eight year long wait for this healing – or even to other themes. Underneath these, however, the story is about baptism. And John’s gospel is often like this – his references are often oblique.

Did you know that the Gospel of John never directly describes the baptism of Jesus by John? But the Baptist does refer to the theophany when he gives witness, saying “I saw the Spirit descend as a dove from heaven and remain on him” (1:32). And only in the gospel of John does the Baptist, seeing Jesus, cry out “Behold the Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world.” This is a pattern with John – he both tells us something we could not know otherwise and also refers only obliquely to the central events we know so well from the other gospels.

For another example, did you know that John never tells of Jesus taking bread and wine, and saying that they are his body and blood? … But it is only in John that Jesus says “I am the bread of life; he who comes to me shall not hunger, and he who believes in me shall never thirst” and “he who eats my flesh and drinks my blood has eternal life, and I will raise him up at the last day.”(6:35, 54). And only in John do we hear of the washing of the apostle’s feet at the last supper. So, once again, John says both less and more than the other evangelists.

Why does John write in this way? I think it may be because he knows full well that he is speaking of a great mystery – a mystery that – like the stars sometimes will – disappears from view if you look at it directly.

I don’t know if you’ve ever experienced this optical phenomenon or not, but it’s not a deficiency in the stars – It’s a deficiency in our eyes. When there is very little light, only our rod cells do the work of seeing. Now, the center of our eye is made up mostly of cone cells. So, if we look directly at a dim star on a dark night, it will sometimes vanish from our view. Whereas, if we look off to the side of it, we will see it with our rod-cell-rich peripheral vision. The star is there whether we can see it or not, but we can only see it when we look at it obliquely.

Now we see as through a glass, darkly. The mysteries are like this. They are ineffable. We cannot speak of them. Not really. Not directly. So, sometimes we have to use our peripheral vision to see the mystery that the gospel of John is teaching us about. And it is in this way that today’s gospel speaks of baptism.

Today, a healing takes place by a pool of water. Our holy father John Chrysostom says of this: “A baptism purging all sins and making people alive instead of dead… [is] foreshown as in a picture by the pool.”[i]

How so? Well here is a pool of water where, time and time again, the sick and suffering have found healing. Often enough that it has become a place famous for healing. The sick who crowd its porticoes are a multitude. This, in fact, is the reason the paralytic man has not been able to enter the pool when the waters are troubled – which is the time of healing – because the others have crowded him out time and time again. The point is, the water is known by this perennial miracle to bring healing.

Chrysostom says that “this miracle was done so that those [at the pool] who had learned over and over for such a long time how it is possible to heal the diseases of the body by water might more easily believe that water can also heal the diseases of the soul.”[ii]

Jesus heals the man not only physically, but he also forgives the man’s sins. We live in two worlds at the same time. We are bodies and spirits at once and the Lord brings us healing in full to our whole being. When Jesus says to the man “See, you are well!” I don’t think he means “well” only in body, for he continues to tell the man, “Sin no more, that nothing worse may befall you.” A worse fate than 38 years of paralysis would be the wages of sin – death and the long death of damnation. Jesus both heals paralysis and tramples death by death – he dies for our sins. Sin and death, you see, go hand in hand – just as do grace and life.

Through baptism, we turn our backs on sin and death and we receive grace and life. We act this out in the rite of baptism itself: Facing West, we reject Satan and sin and death, then, we turn our backs on that and face East and commit ourselves to Christ and grace and life.

Baptism is our way of entering into the resurrection of Christ through the death of Christ. We go down into the water as into a tomb, and we rise out of the water to new life. This is the way Christ has given us to enter into the life in Christ – to be clothed in Christ – to be healed of our infirmities in a truly lasting way – to be forgiven of our sins – to begin life everlasting. And he was already showing us this way when he healed the paralytic man by the sheep pool.

Meaningfully, that sheep pool, according to some ancient authorities,[iii] was so called because it was the place where sheep were washed before being sacrificed in the temple. By entering into this water, then, those who sought healing there were, knowingly or unknowingly, identifying themselves with the sacrifice, which is just what Christ, who the Lamb of God, will do upon the Cross – which is just what we do when we are baptized. This sheep pool prefigures the baptismal font in which we become the sheep of the Good Shepherd.

Another parallel: the water is troubled before the sick, the blind, and the lame enter it for healing (5:7). By whom is it troubled? This gospel passage does not tell us (unless your Bible contains verse 4 of chapter 5. Verse four was almost certainly not written by John, which is why it is omitted from today’s reading). It’s not contained in any of the oldest manuscripts and it contains at least 4 words that John uses nowhere else in his writings.[iv] But I mention it because Chrysostom certainly regarded it as scripture nonetheless – as did other early fathers. And also because I do not believe that just because it was written later by a different author necessarily means that it is not scripture, or that it is not true, or that it is not inspired by God. It reads as follows: “For an angel of the Lord went down at certain times into the pool, and troubled the water; whoever stepped in first after the troubling of the water was healed of whatever diseases he had.”

Now this becomes interesting if we continue to see baptism in this story. Chrysostom says, “The water, however did not heal by virtue of its own natural properties…, but by the descent of an Angel: For an Angel went down at a certain time into the pool, and troubled the water. In the same way, in Baptism, water does not act simply as water, but receives first the grace of the Holy Spirit, by means of which it cleanses us from all our sins.”[v]

Significantly, when the priest calls down the grace and blessing of the Holy Spirit upon the baptismal water, he troubles the water both with his fingers and with his breath. In this way, it evokes the healings at the Sheep Pool.

But notice something else: the paralytic man never enters the Sheep Pool! He had been hoping for healing in the pool but he received instead healing from a direct personal encounter with Jesus Christ. The pool and its healings are an image of baptism, but they are not baptism itself. Baptism, rather, is what brings us – like the paralytic man – into relationship and union with Christ. By it we are identified with Him, and nothing can take that away from us. Let us remember and contemplate our baptisms and give thanks to God for his grace, by which he unites us to himself and saves us from sin and death.

[i] John Chrysostom. Homilies on the Gospel of John 36.1.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] e.g. Augustine

[iv] ταραχή, δήποτε, νόσημα, κατέχω. Raymond Brown says there are 7 “non-Johannine” words, 207.

[v] John Chrysostom. Homilies on the Gospel of John 36.1.

Click here to watch this on YouTube (live stream is at 10am on Sunday, May 3rd, 2020)

People’s book for the Divine Liturgy

Divine Liturgy Propers for the Sunday of the Paralytic Man

Divine Liturgy

Friday – 6:30 PM (If No Vespers)

Sunday – 9:00 AM (Livestreamed)

Vespers

Friday – 6:30 PM (If No Liturgy)

Saturday – 4:00 PM

Parish Address:

4141 Laurence Ave, Allen Park, MI 48101